“Competition brings out the best in products

and the worst in people.” – David Sarnoff

Most people are familiar with the concept of a competitive analysis; it’s a fairly standard business term to describe identifying and evaluating your competition in the marketplace. In the case of UXD, a competitive analysis is used to evaluate how a given product’s competition stacks up against usability standards and overall user experience. A comparative analysis is a term I’ve often used to describe the review of applications or website that are not in direct competition with a product, but may have similar processes or interface elements that are worth reviewing.

Often, when a competitive review is conducted, the applications or websites are reviewed against a set of fairly standard usability principles (or heuristics) such as layout consistency, grouping of common tasks, link affordance, etc. Sometimes, however, the criteria can be more broadly defined to include highlights of interesting interaction models, notable functionality and/or other items that might be useful in the context of the product being designed and/or goals of a specific release.

The Expert Review

Competitive reviews can be done in conjunction with an “expert” review which is a usability evaluation of the existing product. If doing both a competitive and expert review, it’s helpful to start out with the competitive review and then conduct the expert review using the same criteria. Completing the competitive review first allows you to judge your own product relative to your competition.

Why Conduct a Competitive Analysis?

- Understand how the major competition in your space is handling usability

- Understand where your product stands in reference to its competition

- Idea generation on how to solve various usability issues

- Get an idea of what it might take to gain a competitive edge via usability/UX

- If a thorough competitive review has never been conducted.

- When a new product, or major game-changing rebuild is being considered.

- Annually or bi-Annually to keep an eye on trends in your industry and on the web (such as changes in how social networking sites are integrated)

When is a Competitive Analysis Most Useful?

Competitive analysis is best done during early planning and requirements gathering stages. It can be conducted independent from a specific project cycle, or if used with a more focused criteria, it can help with the goals for a specific release.

Limitations of a Competitive Analysis

- A competitive analysis can help you understand what it will take to come up to par with your competitors; however, it cannot show you how you can innovate and lead.

- Insights can be limited by the knowledge level and/or evaluation abilities of the reviewer.

- They can be time consuming to conduct and need to be re-done on a regular basis.

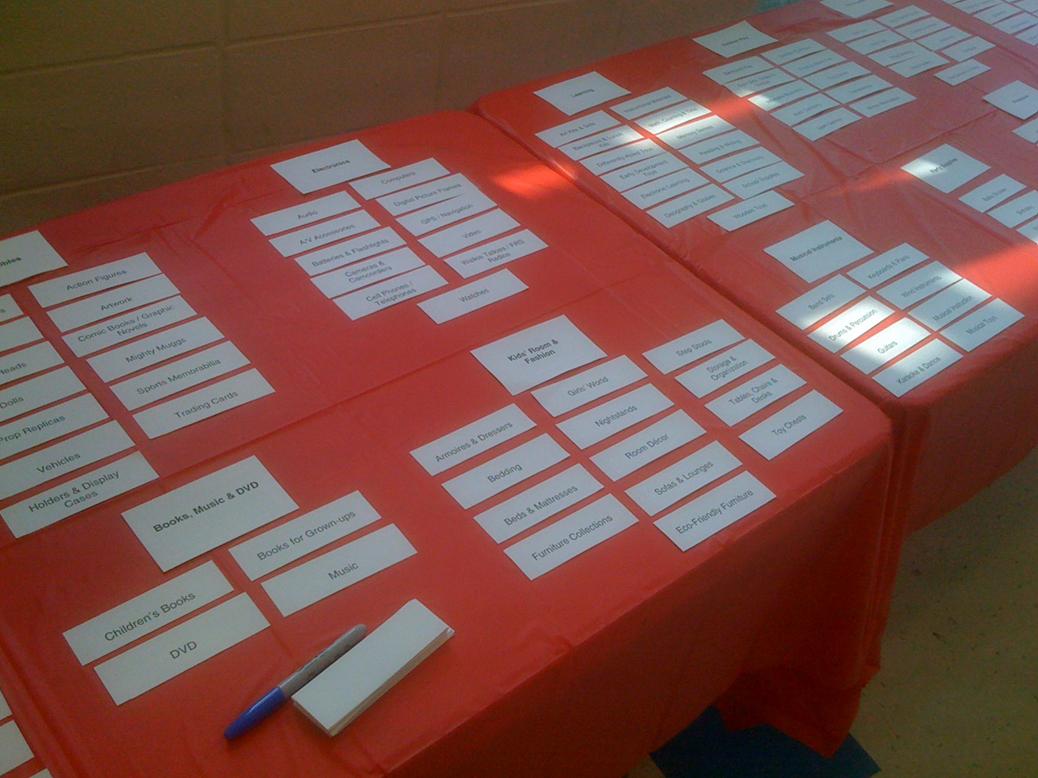

How to Conduct a UXD Competitive Analysis

- Select your competition. On average, I would recommend to target no less than five, but no more than ten of your top competitors. The longer the competitive list is, the more difficult it will be to do a sufficiently thorough investigation. In addition, there becomes a point of diminishing returns where there is not much new going on in the space that hasn’t already been brought to light by a previous competitor.

- Define the assessment criteria. It is important to define your criteria before you get started to be sure you are consistent in what you look for during your reviews. Take a moment to consider some of the issues and goals your organization is dealing with and some hypotheses you uncovered during your audit and try to incorporate these into the criteria as possible. Criteria should be specific and assessable. Here is a short excerpt of a criteria used in an e-commerce site evaluation:

i. Customer reviews and ratings?

ii. Can you wish list your items to refer back to later?

iii. In-store pickup option?

iv. Product availability indication?

v. Can you compare other items against each other?

vi. What general shopping features are available? - Create a Spreadsheet. Put your entire assessment criteria list in the first column, and the names of your competition along the top header row. Be sure to leave a general comments line at the bottom of your criteria list; you will use this for notes during individual reviews. Some of the evaluation might be relative (i.e. rate quality of imagery relative to other sites 1-10), so it is particularly helpful to have one spreadsheet as you work through each of your reviews.

- Gather your materials. Collect the competitive site URLs, software, or devices that you will be reviewing so they will be readily available. A browser with tabbed browsing works great for web reviews. A tip for a mobile device application is that often simulators can be downloaded that allow you to display the mobile device software on your computer.

- Start Reviewing. One at a time, go down the criteria list while looking through the application and enter your responses. It can be helpful to use a double screen with the application on one view and the spreadsheet on the other. Take your time and try to be as observant as possible; you are looking for both good and bad points to report. As you review, write down notes on what you liked, what annoyed you and any interesting widgets you see. Take screen captures of interesting or relevant screens as you do each review.

- Prepare the Analysis. Create an outline of the review document including a summary area and a section for each individual review. Paste the assessment results and your notes from the spreadsheet into the document and use as a starting point for writing the report. You may need to grab additional screen captures of specific things that will be in your evaluation.

- Summarize your Insights. Now that you have the reviews done, you can look back what data pops out as most relevant. Some of the criteria results can be translated into summary charts and graphs to better illustrate the information.

- Schedule a Read Out. Take time to present your findings, setup a read-out for your colleagues. You may want to create a very high-level power point presentation of some of the more interesting point’s from your review. After conducting the read-out, publish your documentation and let people know where you’ve placed the information.

Consider this…

When selecting a list of competitors, instead of just asking, who does what we do? Think about user’s alternatives. Ask, who or what is mostly likely to keep users from using our software or going to our website? While not normally thought of as “competition”, alternatives for an operations support system could be an excel spreadsheet or printed paper forms.

Competitive Assessment Rubric

If you don’t have time for a full written competitive analysis, you can evaluate your competition with an assessment rubric. Because it results in a clear ranking, the rubric is a good “at a glance” way of communicating a software’s relative strengths and weaknesses to clients. Some things to note about this evaluation method:

- It is not a scientific analysis; it’s a short-cut for communicating your assessment of the systems reviewed. Like judging a talent competition, subjective ratings (i.e. “eight out of 10”) are inherently imprecise. However, if you use consistent, pre-defined criteria you should end up with a realistic representation of your comparative rankings.

- When creating the assessment criteria it is important to select attributes that are roughly equivalent in value. In the example below, “Template Layouts” and “Browsing & Navigation” were equally important to the overall effectiveness of the sites reviewed.

The following rubric was created to evaluate mobile phone activation sites, but this approach can be adapted to create ranking metrics for any application.

1. First, create the criteria and rating system by which you will evaluate each system.

| 1 – Poor | 2 – Average | 3 – Excellent | |

| Marketing Commerce Integration | Option to “Buy Now” is not offered in marketing pages or users are sent to a third party site. | The option to “Buy Now” is available from the marketing pages but there are some usability issues with layout and transition | The marketing and commerce sites are well integrated and provide users with an almost seamless transition |

| Template Layouts (Commerce) | The basic layout is not consistent from page to page and/or the activity areas within the layout are not clearly grouped by type of user task. | The layout is mostly consistent from page to page and major activity areas are grouped by task type. Some areas with information heavy content or more complex user tasks deviate from the established layout paradigms. | The site shows a high level of continuity both in page to page transitions and task-type groupings. Information heavy content and complex user tasks are well thought out and intuitive relative to the site’s established layout paradigms. |

| Browsing & Navigation | The site lacks a cohesive Information Architecture. Information is not in a clear top-down hierarchy. There are numerous “orphan” or pop-up pages that do not fit within the site structure. Similar content is duplicated in multiple areas or is presented in multiple navigational contexts. | The site has a structured Information Architecture. Secondary and Tertiary navigation items are related to parent elements, but there may be multiple menus unrelated to the broader structure. There may be orphan pages of detail or less relevant information. | The Information Architecture is highly cohesive. Information is structured with a clear understanding of user goals. Everything has a logical place within the architecture; secondary menus are incorporated into the site structure or clearly transitioned. |

| Terminology & Labeling (Commerce) | Terminology and labeling is inconsistent, confusing, or inaccurate. Different terms are used to represent the same concept. Some terms may not adhere to a common understanding of their meanings. | Terminology and labeling is consistent but could be more intuitive. Some unnecessary industry specific terminology or uncommon terms are used. | Terminology and naming is both intuitive and consistent. Only necessary industry specific terminology is used, in context, with help references. |

2. Next, evaluate the competition along with your own system, scoring the results.

|

|||||

| Marketing & Commerce Integration | Template Layouts | Browsing & Navigation | Terminology & Labeling |

Total |

|

| Our System |

2 (Average) |

1 (Poor) |

2 (Average) |

3 (Excellent) |

8 |

| Company A |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

11 |

| Company B |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

| Company C |

1 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

| Company D |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

10 |

| Company E |

3 |

… |

|||

| Company F | |||||

| Company G | |||||

| Company H | |||||

3. Once your table is complete, you can sort on the totals to see your rough rankings.