“Before I can walk in another person’s shoes,

I must first remove my own.” – Brian Tracy

This article discusses the basics for developing of a set of user personas. User personas are not a research method, but a communication tool. They are a visual, creative way to convey the results of research about the users of your software or website. Personas are fictional characters developed to represent aggregate statistical averages to profile a user group. They do not express all types of user or their concerns, but can give a reasonable representation of who might be using your product and what some of their goals or issues might be. Personas are not fixed precise definitions of your users; they are more of an empathy creating tool. They can help you get into the mindset of a user type and communicate that mindset to others.

One created, personas are a way of humanizing your users and providing a canvas on which you can superimpose ideas on how a given user type might interact with your system. A little bit like criminal profiling (minus the crime and vilification), you can think of it as role playing with the intention of gaining new insights into the other party. User Personas should not be confused with engineering use cases or marketing demographic profiling.

Why develop user personas?

- A key benefit to developing user personas is to provide user-centric objectivity during product design, and reinforce the idea that you and your colleagues’ version of a great user experience is not necessarily the same as your end users.

- User Personas can dispel common stereotypes about users, e.g., the site needs to be so easy to use the VP’s grandmother can use it.

- Later in the design process, user personas can help you communicate the usefulness of a specific design to stakeholders.

While I used to be somewhat limited in using persona, I did create them a few years ago for a top-five business school. The project was in the context of a site redesign that included an overhaul of the site’s information architecture. I conducted a fairly exhaustive audit of the MBA space which included a competitive review, expert review, and stakeholder interviews. At the time, I didn’t create personas for myself, I just used the underlying audit data to restructure the site’s content and define a simplified navigational model. However, later, when preparing to present the new information architecture to the client, I took the time to create a set of user personas based on the original data I used to make my design decisions. They were created out of a need to help illustrate to the client how the new structure better addressed the needs of their prospective students, and to assure them that user’s concerns were being addressed. After realizing how effective persona can be for stakeholder buy-in and alignment I have since used them much more frequently in a range of UX projects.

When are personas most useful?

- User personas are useful when there are a number of unsubstantiated assumptions floating around about who your users are. E.g. early adopters, soccer moms, the VP’s grandma, etc.

- When there is a tendency for developers and product managers to make design decisions based on; their own personal preferences, technical constraints, chasing short term sales, or any other reasoning that does not consider the end user.

- When there is a general lack of clarity about who your end user is, or when the data you have regarding your users does not seem to directly translate into insights about their behavior.

- Whenever you need a communication tool to advocate and encourage empathy for end users.

Development Lifecycle

Persona creation is best done during requirements gathering stage. However, getting the most out of your user personas means that they should also be referenced during development and testing, as questions and changes arise. They should also be compared to, and updated against actual user testing and post-release feedback. If properly evolved and maintained, personas can be an effective guidepost throughout the development and product lifecycle.

Limitations of User Personas

- It’s easy for personas to be taken too literally or become a stereotype. Personas should never be considered a definitive archetype of your users, doing so runs the risk of turning your definitions into pseudoscience, akin to phrenology. Direct user testing and feedback insights should take precedence over anything user persona derived.

- User personas are not precise; they are limited by the innate prejudices, interpretations, and reference points of the authors of the personas and any subsequent user scenarios.

- User personas are not an appropriate communication tool for everyone; some people prefer a well crafted presentation of the source data over a persona which can be perceived as containing superfluous data.

How to implement user personas

With a little research, a set of basic personas is actually fairly easy to put together. The first step is to pull research from multiple sources to gather data about potential users. Next, synthesize this data to form user groups and select representative data from each user group to form a user data profile. Finally, add supplemental character information to create a believable persona. As a general rule, you should start with trying to define three to five user types, adding additional types as appropriate. I would recommend against defining more than about eight or 10. Beyond this number, you start to exceed people’s ability to reasonably keep track of the information.

Consider This…

If you think you need more than ten personas, or have already been heavily relying on personas to drive development consider as a next step investing in an ethnographic study. Real profiles and insights derived from the results of an ethnographic study will provide more actuality than fictitious personas.

- Conduct Research. Pull together any reliable data you can find might describe your users or give insight into their goals, concerns or behaviors. Collect any potentially relevant demographics such as; gender, age, race, occupation, household income. Let’s, for example, take the case of developing personas around prospective MBA students. In addition to client interviews I was able to pull a large amount of key data from sources on the Internet. Some references I found were:

- Graduate Management Admissions Council

- GMAC: 2004 mba.com Registrants Survey

- The Black Collegian: ‘The MBA: An Opportunity For Change’

- The Princeton Review: ‘Study of Women MBAs’

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES)

- Form Relevant User Groups. To continue with the business school case study, research on MBA students showed that there were a growing number of minority women enrolling in MBA schools. In addition, the client indicated a desire to further attract this type of student. Armed with that initial seed data, I defined a user group of minority women who were considering, had applied to, or attended business school. Further research allowed me to compile a list of statistical information about this group (such as average age, current occupation, family status, etc) as well as formulate some ideas about their interests, concerns and expectations. When compared to more “traditional” MBA students, these women were; a few years older on average, more likely to be married with children, and were highly-focused on what specific opportunities this type of degree offered post graduation.

- Create and Embellish the Persona. Start by turning the data you have for the user group into a single individual. The “Minority Women” user group was converted into a thirty six year old, African American woman named Christine. At this point it’s ok and actually preferable to fill in the gaps with plausible details about this person to bring them to life a bit; e.g. “Christine Barnhart is a marketing communications manager who balances her time between work and family…” Since this is in large part a tool to facilitate empathy for the user group, as much realistic information as possible should be incorporated to develop the character. As long as the “filler” is not negated by other data it should be fine. Even still, after you have finished writing your personae take a step back and ask yourself; “Is it reasonable to expect this person to exist?” Alter your description if necessary, or move on to the next persona.

- Develop and Test User Scenarios. Now that you have your personas and an idea of what your user types are, we can make some assumptions about what functionality or information they might find useful. You will need to develop some User Scenarios to help test any hypothesis you have. Unlike a use case, which is a description of how system functionality interacts (i.e. contact data is retrieved, error message is returned), user scenarios focus on the user’s perspective. A simplified User Scenario for our “Christine” persona might look like:

- While successful in her career, Christine is not entirely sure she has the background and experience to be admitted to a top business school. In addition, she has a lot of specific questions about the program’s culture. She is concerned that it may be too aggressively competitive for her to get the most out of her business school experience.Christine goes to the program website and immediate looks at the eligibility and admission requirements. She takes her time looking through the information and prints out a few pages. Next, she starts to browse around through site, trying to get a feel for the culture. She finds a section that has video interviews with students and so she watches a few and begins to get a sense of whether this school is a fit for her or not.

User Stories Not to be interchanged with a user scenario (or use case), a user story is a short two or three sentence statement of a customer requirement. It is customer-centered way of eliciting and processing system requirements within Agile development methodologies[1].

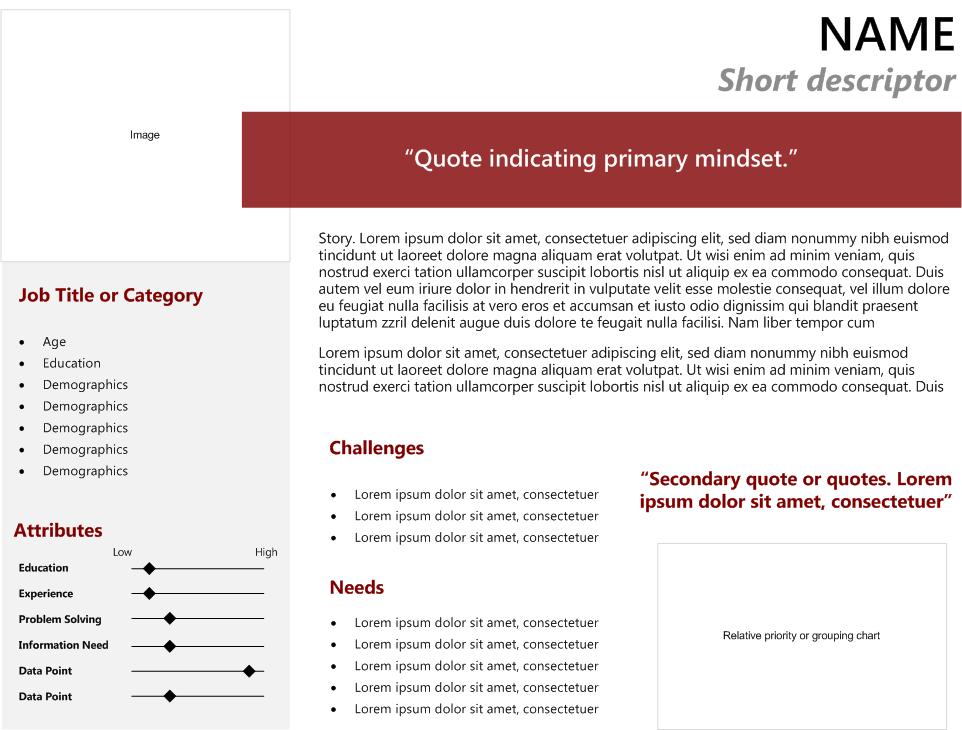

Basic Persona Template

There are a wide range of user persona templates, and they can get rather complicated. Considering that the intention of this type of tool is effective communication, I tend to gravitate toward the clean, simple layouts that are one page or screen. Below is a basic example template. Don’t get too focused on templates however, if you find information that you think is useful or relevant but it doesn’t fit your template, rework the template to fit the data.

[1] More information on user stories can be found at: http://www.extremeprogramming.org/rules/userstories.html